Project Description

NEWS

Participatory approaches towards GEP design and implementation guide

Based on the experience of the SUPERA, Yellow Window developed a guide on how to facilitate participation from stakeholders in the design and implementation of Gender equality Plans (GEPs). The document builds on the one hand on a project deliverable that was made available to the SUPERA core teams in each GEP implementing institution at the start of the project, and on the other hand on the actual experience of using these techniques. It aims at providing guidance to all those who will implement Gender Equality Plans on how to proceed with this type of techniques.

This publication is meant as a reference document and guide for all who intend to use participatory techniques. The target of this publication are the members of the core team in charge of the GEP inside an institution, as well as those acting as change facilitators.

Download the Participatory approaches towards GEP design and implementation SUPERA guide [file .pdf]

Visit the web page dedicated to participatory techniques

E-learning training modules on gender equality for R+D+I financing activities

The Spanish State Research Agency has issued a series of e-learning training modules on different aspects of gender equality in R+D+I, developed in collaboration with the Women and Science Unit of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, as part of the actions foreseen in the I Gender Equality Plan of the Agency 2021-2023.

Visit the page on the website of the Spanish State Research Agency: E-learning training modules on different aspects of gender equality in R+D+I, for R+D+I financing activities

Visit the section dedicated to training resources on the website of the Spanish Ministry of Science and innovation: Recursos didácticos

Here is the full list of video trainings (in Spanish language, with self-generated English captions):

What comes next? Sustainability of structural change for gender equality after SUPERA

By María Bustelo, Universidad Complutense de Madrid and SUPERA Coordinator

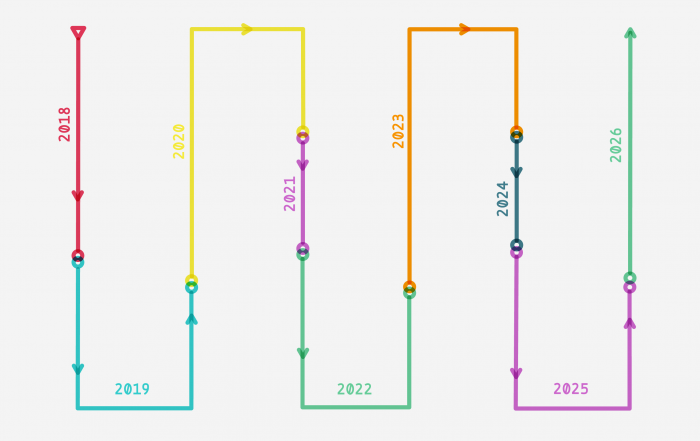

SUPERA is finally coming to an end after four years of being working together. It seems quite far away now those days in early June of 2018 of the kick-off meeting. As I said in the opening of our Final Conference in Madrid last March 25th, looking back now, what four years! We can definitively say that it has been a long and winding road. Throughout this four-year period, quite intensively during the first 18 months of the project life, we faced important institutional and political changes in all our implementing partners. And the pandemic precisely caught us about to hit the midst of the project when we were just finishing the take-off and reaching the cruising speed. All these circumstances made us be constantly adapting our strategies, interventions and change processes to the different contexts, and they also made us highly resilient.

But all in all, SUPERA has also been, beyond an enormous challenge, a fabulous adventure, full of efforts, achievements, and inspiring practices of which we are proud. It has also represented the best of working together, supporting each other, strengthening previous and establishing new professional bonds, which I am sure, will last well beyond the end of SUPERA.

The SUPERA consortium resulted a balanced formula of Research Performing Organizations (RPOs), in this case, four universities, and two very different Research Funding Organisations (RFOs), as we understood from the beginning that gender+ structural change should also be enhanced by how research money is distributed. Although with different logics and being respectful of our different idiosyncrasies, we have had excellent exchanges, used synergies, and learnt a lot from each other. The other wise choice of the SUPERA consortium was to count on two excellent supporting partners, one, Yellow Window, for training and guiding us through innovative methodologies and resources, and Science Po, as an embedded formative evaluator providing soundly continuous feedback to the implementing partners. For me, it has been a pleasure and an honour to coordinate this excellent consortium.

So, what comes next? How does SUPERA ensure sustainability? Sustainability has been one of the four core principles with which SUPERA was designed and developed. But the other three: cumulativeness, innovation and inclusiveness also contribute significantly to the sustainability of the project.

The first principle we wanted to observe from the design and inception of the project was cumulativeness. It was about taking advantage of what was already there, not trying to reinvent the wheel. Therefore, SUPERA was drawn upon tools & instruments already experimented and evaluated by other experiences and structural change projects. Moreover, throughout the project, we have continuously exchanged with other sister projects, encouraging, and participating in joint initiatives and campaigns, common seminars, and webinars. This has been facilitated by the fact that several partners in the SUPERA consortium participated in other past projects, and the others will continue to contribute to future ones. And SUPERA leaves several materials, methodologies developed, and documented inspiring practices that will contribute to this common European legacy.

The second principle, that one of innovation, made us develop innovative implementation structures using transformation design techniques, as Gender Equality Hubs and Gender Equality Fab Labs, which were thought for designing, prototyping, and testing affordable and innovative policy solutions to gender bias and imbalances identified through gender audits and diagnoses. Gender Equality Hubs, adapted to each institutional context, have been the most important key actors for launching and enhancing gender structural change processes at SUPERA implementing institutions. Gender Equality Fab Labs have also been an interesting and useful resource, which was used productively in different formats and for various topics by all partners. What we learnt from the SUPERA experience is that the initial diagnoses that were planned and successfully performed during the first year of the project, were also needed to be monitored in a continuous manner throughout the project. The reasons for that are the invisible and many times difficult-to-grasp character of gender+ inequalities, as well as all the confronted political, institutional, and global changes (pandemic included). This need of constant and updated information strongly incentivized us to prioritize, from the beginning, the promotion of sustainable and stable gender management information systems.

The third principle, inclusiveness, is at the core of our methodology and has strongly defined the SUPERA spirit. It means that we are absolutely convinced that the only way for reaching a real structural change is through the involvement of the entire research & university communities. Therefore, in SUPERA we have emphasised the importance of using participatory techniques and active stakeholders’ involvement, as this really increases their support to change processes and helps to reduce resistances. This conviction alludes also to the need of reaching everyone in the community, including men and all genders, without requiring the feminist or gender expert “card” to entry the club: the real sustainable change starts when non previously gender advocates become gender+ allies and change agents. And after four years we can say that we are very proud as, beyond the core teams, the SUPERA communities in partners’ institution are huge and diverse.

Coming back to the fourth SUPERA core principle, sustainability, from the beginning of the project we committed to design, implement, and evaluate interventions whose results have chances to endure over time producing gender structural change in our institutions. For securing this sustainable institutional change, we have done efforts towards project top management endorsement apart from the visibility of actions in our institutions, and the inclusive long-term involvement promotion explained above.

Another hard-won lesson learned from SUPERA is that the necessary top management commitment and endorsement should be always combined with bottom-up approaches from the communities. These last ones are so important that, if already started, they can remain being the change driving force when the first one disappears, or that well combined with adequate institutional political will, they can have amazing multiplying results. In all partners institutions, most of the participatory structures and networks created by SUPERA will remain in place and keep on being important change drivers. This is the case of the Gender Equality Nodes network at UCM, with representatives in all the 26 UCM Faculties, which has been increasingly active in gender promotion activities at the UCM towards the end of the project. For instance, as a result of a Conference on how to integrate a gender perspective in teaching organized by this Network with SUPERA support, an edited guide with recommendations for integrating gender in the areas of STEM, Social Sciences, Health Sciences and Art & Humanities will be released at the UCM very soon. But even going beyond SUPERA, this Network promotes a true interdisciplinary approach to gender by participating together in an innovative gender-sensitive pedagogical project and in another one for studying classroom student participation for the UCM Student Observatory. No project team at the UCM had ever covered so many faculties and areas before.

SUPERA also leaves concrete outputs, as for example, the already disseminated the Tailor-mage guides for gender-sensitive communication in research and academia, highlighted as a key good practice in the field in the newly updated version of the GEAR (Gender Equality in Academia and Research) online tool by EIGE. Other examples from SUPERA are also referenced in the GEAR tool, Gender Equality Fab Labs and the Gender Equality Nodes network at the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM). At the end of the project this month, SUPERA will also submit the last public deliverables, among others, Guidelines and best practices for RPOs and its version for RFOs. Also, several participatory and co-creation techniques have been developed and adapted by YW under SUPERA, like journey maps, lotus blossoms, stakeholder mapping, cause diagrams or personas, and guides and edited materials on those techniques will be uploaded and made available in the SUPERA web for further use by the structural change community.

As part of our resilient response to the COVID-19 crisis, as part of SUPERA, Central European University (CEU) provided the senior leadership team with a list of recommendations for a gender-sensitive implementation of telework in relation to COVID-19 pandemic, while the UCM performed a Survey on working conditions, academic time usage perception and academic performance during the COVID-19 crisis, which was also adapted by the University of Coimbra (CES-UC) and the University of Cagliari (UNICA). Their results have been already disseminated in reports, conferences, and future academic publications.

At the level of implementing partners, key initiatives have leveraged change beyond SUPERA organizations. This is the case of the network of regional research funding bodies committed to advancing gender equality and mainstreaming gender in research set up by the Spanish Research Agency (AEI- Partner MICINN), in a country where regional governments have significant agency regarding higher education and research. At the Autonomous Region of Sardinia (RAS), a regional research funding body granted with specific capacities under Italian Law, the SUPERA-driven Gender Equality Plan was taken up as an opportunity to mainstream gender not only in research funding calls, but also for structural funds, at a time when the insular region receives considerable funding through the EU recovery plan. This impact also leverages the leading role the two Sardinian partners (both RAS and UniCA, this last one being the largest university of the Island) are taking in building a gender sensitive research eco-system in the region. Also, in Portugal, SUPERA has been the driving force in establishing Coimbra as a pioneering university, actively sharing practices and knowledge also with national gender equality policy stakeholders, at a time when parity laws became applicable to higher education and research bodies. As an example, during the latest legislative campaigns, Coimbra University’s Vice Rector for Research publicly engaged Prime Minister Pedro Costa with the gender dimension in research as a topic for his next term.

Summing up, SUPERA leaves six Gender Equality Plans in our six implementing partners, but also important changes and structures in our institutions that go beyond those plans. We leave materials, reflections, and inspiring practices as well as active professional bonds and networks that feed and contribute to the European structural change and sister projects’ community. We also leave a good group of colleagues who became good friends while struggling together to make the best of the project during difficult times. I am sure all of these will continue to impact our institutions and our personal and professional lives beyond the end of SUPERA.

Inspiring gender equality: the new institutional videos are online!

By Valentina Citati and Paola Carboni, University of Cagliari

After a huge collective selection and editing effort, the SUPERA Consortium identified some of the most inspiring practices developed during the 4 years of our project, and collected them in a new institutional video, together with selected highlights of the values and methodology that inspired our approach.

The work, developed with contributions from all partners and coordinated by UNICA, produced an institutional full video and 9 short extracts of the inspiring practices from each partner.

Cumulativeness, innovation, inclusiveness, sustainability: in the first short extract our Coordinator María Bustelo presents the four key principles that inspired the work in Supera with the aim to promote institutional change for gender equality.

In the second video “Capacity building, training and support”, Lut Mergaert (Yellow Window) explains how the application of co-creation and participatory techniques supported the promotion of institutional change for gender equality throughout SUPERA, becoming a key success factor and a source of inspiration for the partners implementing gender equality plans.

Tara Marini presents the initiatives foreseen by Regione Sardegna to support female researchers: for instance, the use of gender-sensitive language in the funding calls, and the introduction of a section dedicated to ensure gender balance.

In the video Working Group on #genderequality in R&D&I funds Angela Martínez-Carrasco tells about the experience promoted by MICINN with the development of a roadmap for the integration of a gender dimension in the planning and evaluation of R&I strategies, programmes and calls for proposals.

Ester Cois explain the institution of the Delegate for Gender Equality in UNICA: a key step to promote gender equality in the university.

Mónica Lopes’ video presents the Coimbra University’s strategic plan to ensure gender equity, an innovative and transformative measure to inspire other universities in inclusiveness and equality.

Paula de Dios presents the experience developed by the Complutense University with the gender equality nodes network.

The importance of CEU’s New policy on harassment and its innovations is described by Ana Belèn Amil, with highlights on how to increase the effectiveness of the policy itself and the trust of the academic communities in reporting cases.

Finally, Maxime Forest, SUPERA internal evaluator (Sciences Po), explains the role of monitoring and evaluation for the gender equality plan development.

The invitation is to watch, share and be inspired by the practices and tools for promoting gender equality narrated in our videos.

Feminist project management in Covid-19 crisis

By Paula de Dios Ruiz, Universidad Complutense de Madrid and SUPERA project manager

One of the main challenges of the SUPERA project has been grappling with Covid-19 crisis. At the beginning of the project, we were planning to implement several activities with the conviction that face to face discussions were crucial to change mindsets and policies. Suddenly, in March 2020 the Covid-19 crisis led to emptiness of campuses and the imminent shift toward remote work.

SUPERA partners were used to working online among our international Consortium, thus we rapidly transferred our local activities to online formats, using new online tools to continue our co-creation processes of GEPs design, however new challenges emerged that so far no one had experienced before.

During the tough lockdown period, the main problem was to balance personal and professional life; as a consequence of that, gender inequalities in research and academia were aggravated, as the surveys conducted by our institutions revealed. However, this has not been the only consequence of Covid-19 crisis.

In the following list, I would like to highlight some lessons learnt during the last two years of project management in times of Covid-19 crisis.

- If someone is not answering my emails or complying with deadlines, I should address the situation with flexibility and understanding, because there is a wide range of particularities affecting every person in these times, especially women with care responsibilities.

- Online tools are not user-friendly for everybody, so it is important to be patient and supportive and avoid awkward situations. Feeling clumsy in online meetings could lead to lack of participation and, due to gender and age technology gaps, we can infer who will be less involved.

- Online meetings, as well as face-to-face ones, require facilitation and time management. Since the Covid crisis started, a lot of meetings have been set up with no clear aim, just because it’s easy and convenient to arrange one. However, without a clear agenda and goal, meetings easily become time consuming and frustrating, so it’s crucial to prepare them in advance and avoid overtime and online fatigue. Taking into account that at certain moments it’s highly likely that participants (especially women) are simultaneously at the meeting and taking care of someone at home. Thus, every time a meeting is held, have a clear objective, agenda and stick to the time allotted.

- Additionally, it’s important to facilitate meetings in which we guarantee attendees´ total participation. It goes without saying that it’s pretty easier to be mute in a virtual meeting than in a face-to-face one. Women tend not to speak out as often as men do. In view of this fact, I strongly recommend putting into practice participatory techniques. A good example of this would be to let participants know in advance that a round of opinions will be asked for. Another tip would be to use the chat box instead of giving the floor, which will make participation more inclusive.

- Mental health problems have always existed, however since the outbreak of Covid-19 there has been a dramatic surge of these cases of anxiety, stress and depression. Consequently, medical leaves have kept soaring drastically. Therefore, we should be aware of this reality and treat it respectfully, with confidentiality and avoid stigmatizing.

- Sexual harassment and gender based violence has been still ocurring eventhough we are all telecommuting. Therefore, as always, we must be sensitive, act in those cases where we have clear evidence and be supportive to women at risk of violence.

- This crisis has been experienced in different ways by each of us, depending on each one’s family situations, health conditions, place where we live, loss of close relatives due to Covid, hospitalization due to Covid… As a consequence, each one has different perceptions of risks, concerns, vaccination status and willingness to establish higher or lower prevention measures. If we are planning a presence event we must deal with this diversity, discuss it openly and not put anybody in an uncomfortable situation, or expose anyone to risks without previous agreement.

All in all, a feminist approach in project management is a must when we are working on gender equality projects which, in my opinion, means that we must understand and boost diversity, give value and visibility to all types of knowledge and put care responsibilities and live needs at the center of our managament, because feminist theory must be put into practice also in management practices.

Mutual learning & exchange between RFOs to foster institutional change: webinar recording available

Date: Thursday, 21 April 2022 at 10.00 – 11.30 Central European Summer Time.

This webinar will take the format of a facilitated exchange between less advanced and advanced organisations, where the first will pose questions related to setting up and implementing a GEP (e.g. how to start, how to set up a team, how to decide on priorities, resources to foresee, how to mobilise internally, etc.) and the second will try to address the questions presenting their experience. The duration will be approximately an hour with the participation of four RFOs. The session will be offered to the SUPERA GEP implementing partners and it will be opened to interested RFOs across Europe.

Learning objectives:

- Mutual learning and exchange: getting inspiration from others with examples of promising practices

- Present the pitfalls and strengths of applying institutional change in RFOs

- Inspire about possible benefits and interventions

Invited speakers:

- Laurence Guyard, Responsible for relations with scientific communities, ANR (Gender-SMART project)

- Donia Lasinger Deputy Managing Director & Programme Manager, Vienna Science and Technology Fund, WWTF

- Nadège Ricaud, MSCA National Contact Point, Contact Person for Gender Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique, FNRS

- Elena Simion, International Projects Expert, Executive Agency for Higher Education, Research, Development and Innovation Funding UEFISCDI (CALIPER project)

Agenda

10.00-10.10 Welcome / Expectations about the webinar

10.10-10.40 4 RFOs presenting their journey

10.40-11.00 Facilitated Q&A between the RFOs

11.00-11.30 Q&A and wrap-up

The webinar recording is accessible via this link on the SUPERA YouTube channel.

Engaging with external stakeholders and innovation ecosystems: recording and presentations available

Friday, 8 April 2022 at 11.00 – 12.30 CET

This webinar aims at presenting the experiences of working with external stakeholders and the innovation ecosystem while implementing a Gender Equality Plan. Capitalising on the knowledge gained from our sister projects, Gender-SMART and CALIPER, the webinar will present the benefits of this collaborative approach which could be structurally built into the GEPs process to foster institutional change.

The session will be offered to the SUPERA GEP implementing partners and will be open to sister projects. The webinar will take the format of two presentations of approximately 20 minutes each, followed by a question-and-answer session facilitated by two facilitators.

Learning objectives:

- Provide examples of promising applied solutions and familiarise with existing promising practices

- Inspire about possible benefits in institutional change from working with external stakeholders

- Inspire about possible interventions with current and new partnerships

Invited speakers:

- Panayiota Polykarpou, Project Manager at CUT for the Gender-SMART project Download the presentation by Panayiota Polykarpou

- Maria Sangiuliano, CEO and gender expert at Smart Venice, Scientific coordinator of the CALIPER project Download the presentation by Maria Sangiuliano

Facilitators:

- Lut Mergaert & Vasia Madesi (Yellow Window)

Agenda

11.00-11.10 Welcome / Expectations about the webinar

11.10-11.30 Presentation: Working with external stakeholders at CUT

11.30-11.50 Presentation: The quadruple helix innovation ecosystem of CALIPER project

11.50-12.20 Q&A

12.20-12.30 Wrap-up and evaluation

The webinar recording is accessible via this link on the SUPERA YouTube channel.

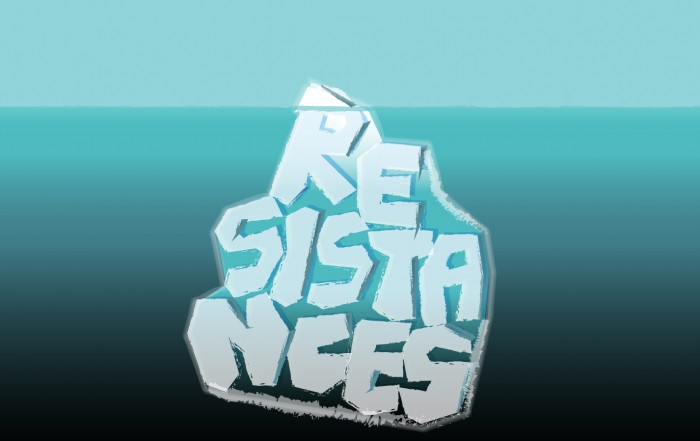

How do we deal with resistances to structural change in gender equality in higher education?

By Lucy Ferguson, Yellow Window

We know that resistances are a normal and necessary aspect of structural change for gender equality. As Fiona Mackay argues:

“We should celebrate as a success cases where the status quo has to start to work hard to reproduce itself and has to invest resources and energy in resisting gender change. The need for visible resistance to positive change is a success. It is evidence of the chipping away of patriarchy; it might be chipping away really slowly, but it is changing.”[i]

However, for many of us, the daily practice of dealing with resistances is challenging, and often exhausting or demotivating. The recently published Toolkit: Resistances to structural change in gender equality – co-authored with Lut Mergaert – was developed in order to support for those implementing structural change in higher education institutions to deal with resistances in their work. While reading the Toolkit, we invite you to reflect on a couple of key questions: How do you currently deal with resistances? How could you deal with resistances differently?

The Toolkit draws on the collaborative efforts of a range of H2020 structural change projects – particularly SUPERA, GE Academy, Gender-SMART and GEARING-Roles. It incorporates the learnings and reflections from three in-person and two online workshops on dealing with resistances, as well as a SUPERA project webinar which followed up on the resistances toolkits developed during the in-person workshop. Following these workshops, the majority of participants reframed their thinking by acknowledging that resistances are a normal and necessary part of change. They also agreed that resistances are something which can be managed, and felt encouraged to be subversive and strategic, often within unfavourable or challenging political circumstances. The Toolkit is organised in three sections: Categorising and theorising resistances; Common guidelines for dealing with resistances; Resistances Action Plan.

Categorising resistances – why, how, who?

Building on previous work developed by the FESTA project[ii] as well as other research, the toolkit presents a set of examples and questions to help readers understand how to categorise the resistances they are experiencing when implementing their Gender Equality Plans (GEPs) and structural change programmes. Reasons why resistances are being experienced include a wide range of aspects, such as, for example: limited human and financial resources; conflicting interests and priorities for funding; lack of capability; not knowing how to do it or uncertainty on how to start; gender blindness; and a perception that gender equality has already been achieved. As shown here, resistances are not always specifically about gender equality per se. Indeed, as discussed during the workshops, our assumptions regarding what is behind resistances may at times be arbitrary and not necessarily reflect the actual reasons for resistance.

Resistances to structural change can be manifested in a number of different ways – which can largely be categorised into active/explicit and passive/implicit. Active or explicit resistances tend to be easier to identify, such as: hostility, sexist humour, devaluation and disparaging women’s accomplishments or professional commitment, interrupting, denial of access to resources, etc. Further expressions of explicit resistances include: “essentialist” discourses about gender inequalities; depoliticising and marginalising gender inequality arguments and data as a matter of contrasting opinions, rather than “facts”. In contrast, passive or implicit resistances can be more difficult to identify and address. These include: making procedures more difficult, limiting access to institutional resources, providing mere lip-service support but nothing else, etc.

In terms of who is creating resistance to structural change, individual resistances come from a single person, more often from men, although not exclusively. Group resistances can also be identified, such as a specific department or group of colleagues within a department. As discussed in the workshops, institutional – as opposed to individual or group – resistances are more difficult to address, as they tend to be a product of institutional culture or an institution’s legal or administrative procedures. Moreover, the superficial or preliminary manifestation of resistances may be seen differently as the implementation process develops. It should be noted that in some workshops, participants found it more difficult to identify institutional resistances compared to individual.

Common guidelines for dealing with resistances

The Toolkit presents the collective work of participants in the resistances workshops. In terms of caring for the “core team”, an emerging theme in structural change projects is the lack of recognition of “academic care work”. In order to acknowledge this, the Toolkit develops the “Four Ss (for us)” approach:

- Success – celebrate small wins to help motivation

- Sanity – use energies where they can have most impact

- Self-care – look after each other’s well-being

- Sustainability – bear in mind this is a long-term process

Within the ‘For Us’ approach, participants developed the Anticipate – Prepare – Rehearse strategy. Rehearsal involves practising arguments and counter-arguments and learning to communicate politically – for example, use of role plays has been particularly useful. As set out in the Toolkit, role plays can be used by the core team to practice particularly challenging or stressful situations in advance, managing reactions and preparing strategies. More broadly, in order to tackling resistances to implementation, the Toolkit discusses the following aspects: develop tactics and strategies; build networks and alliances; learn to deal with bureaucracy; and improve arguments and communication.

Resistances Action Plan

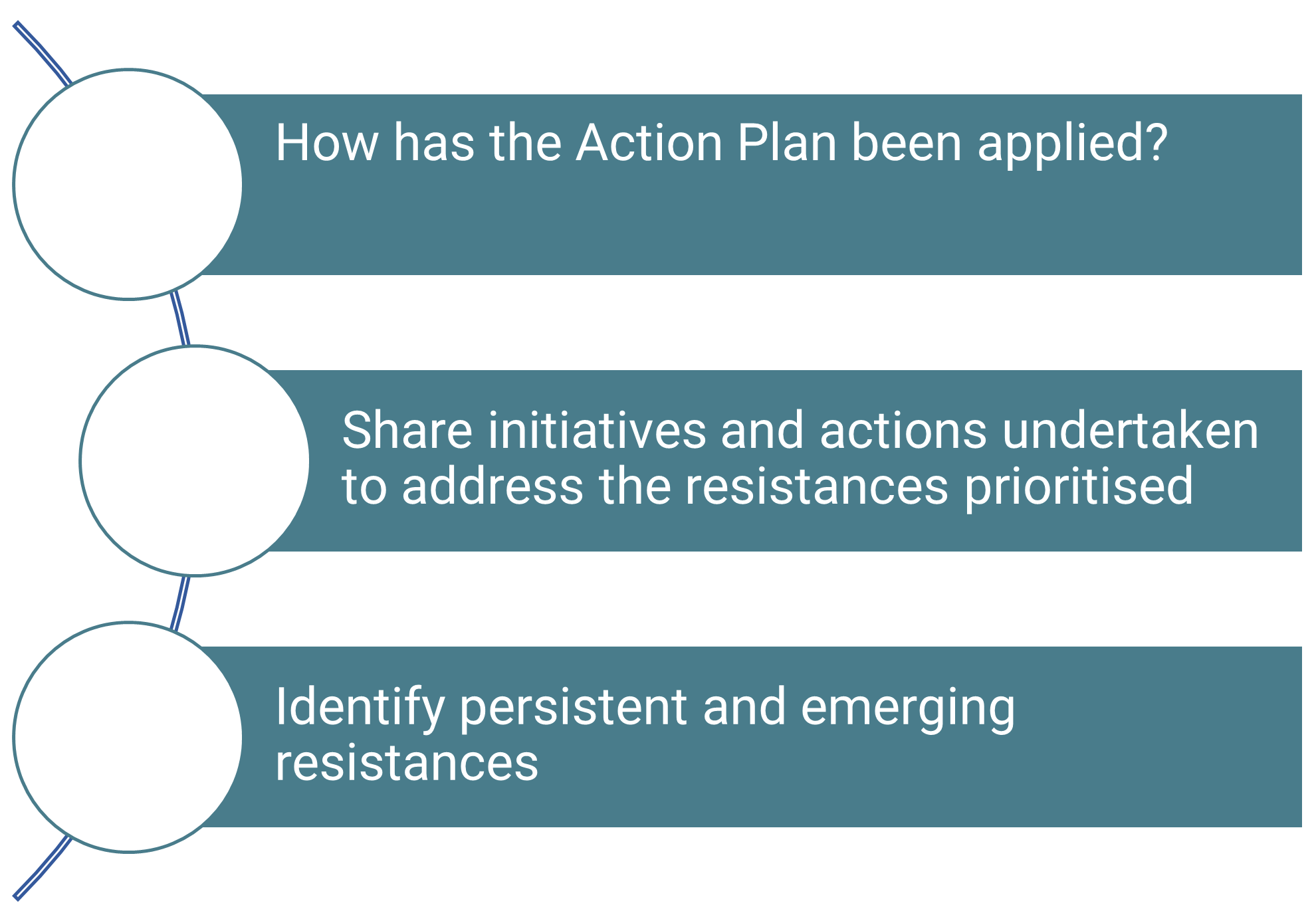

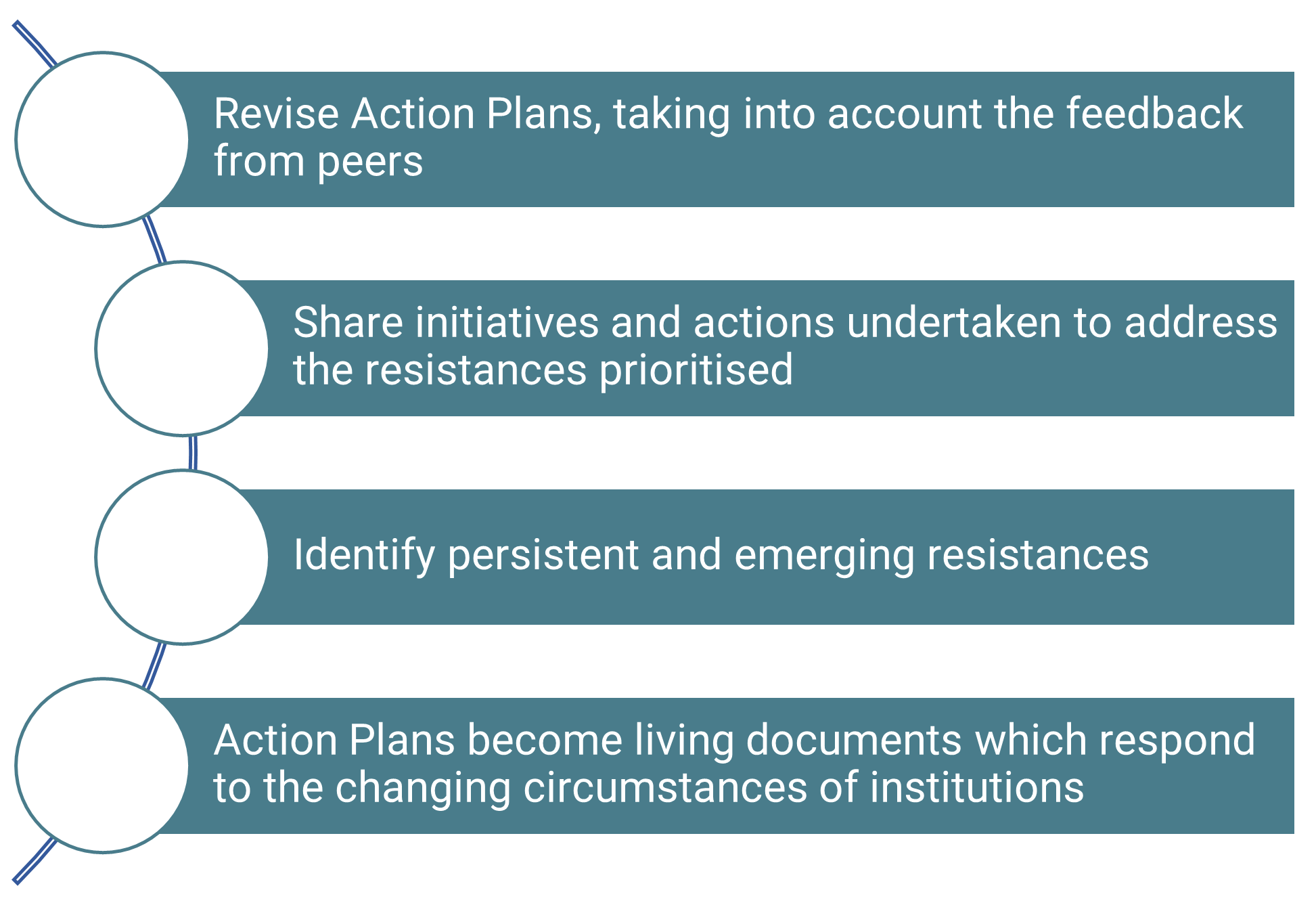

Finally, the Toolkit presents an Action Plan, composed of five stages: Identify and Categorise; Prioritise; Conduct a Follow-up Session; Revise.

Stage 1 – Identify and Categorise

Stage 2 – Prioritise

Stage 3 – Follow up Session

Stage 4 – Revision of Action Plans

We invite you to use the Toolkit to support your ongoing efforts in structural change for gender equality. The full document can be found here at this link.

[i] Fiona Mackay, quoted in Aruna Rao, Joanne Sandler, David Kelleher, Carol Miller (2016), Gender at Work: Theory and Practice for 21st Century Organizations, Routledge

[ii] Saglamer et al. (2006), Handbook on Resistance to Gender Equality in Academia, available at: https://www.festa-europa.eu/public/handbook-resistance-gender-equality-academia

From training the trainers to training the community: the experience at CES-UC

By Cláudia Araújo, Universidade de Coimbra

Throughout the duration of SUPERA, all Consortium members devoted significant efforts to training and capacity building, as, from the beginning, our project was about improvement: improving our institutions, improving the wellbeing of our communities, but also improving ourselves, as academics and as human beings. Our starting point at CES-UC was one of general lack of awareness and expertise on gender equality in academia by key stakeholders, as well as absence of institutional action or mandate in pursuing gender equality, so we were aware that our work would necessarily include training and capacity building.

The participatory approach to these activities developed in the Consortium was a fundamental step in pursuing this multifaceted improvement.

Training the trainers

Although the core team at CES-UC was well versed in gender equality in higher education institutions, and experienced in delivering training, participation in the first training sessions organised within the Consortium constituted a much-valued opportunity for obtaining new skills and gaining new insights. We appreciated the hands-on approach to acquiring knowledge, the experienced gained on working with an array of participatory techniques that we then applied in our own university, and enjoyed mobilising our creativity to design collective outcomes that could be adapted to our own institutional context. It was also an opportunity to engage partners from the University’s central services that would be able to multiply efforts across our organisation: for example, the HR Officer, selected with the purpose of fostering her ability to incorporate GE in her work, as well as her engagement with GEP implementation or the Head of the Planning Division, whose in-depth practical knowledge about the structures and procedures of the institution made him a valuable asset for foreseeing and navigating resistances.

These training sessions were also excellent opportunities to build a more personal relationship with the teams from the other universities, research funding organisations and expert partners. The added value of the personal interconnections built during these sessions cannot be understated: as we faced challenges, resistances and difficulties during the implementation of the project, we knew we could benefit, from the start, from a strong inter-institutional support network that we could rely upon – even in such unprecedented pandemic times.

We also took part in training sessions promoted by sister projects, such as the GE Academy, that were also valuable in enriching our experiences and building our capacities to pass on valuable knowledge to our own community at CES-UC, but also to network and expand our horizons.

Training the community

The Supera team at CES-UC run multiple training sessions, workshops and co-creation actions since Supera’s inception. We chose to articulate traditional exposition-based training with co-creation techniques, as that stood as the most appropriate path for our institution. That allowed us to provide innovative spaces of knowledge creation, with the participation of multiple members of the academic community: students, research and teaching staff, technical and administrative staff, and institutional leaders. We were thus able to create participatory venues where they were lacking, and support participants’ efforts in co-designing solutions for complicated gendered problems, that we then streamlined to decision-makers in the university, in the form of specific recommendations/ guidelines/ checklists. This practice also created a much valued avenue of engagement and open discussion, enabling further networking for gender equality across the institution.

This alliance-building and stakeholders empowering work was rewarding for both trainers and trainees, and the multiplying effects of the sessions cannot be diminished. We received very good feedback from our participants, who often returned for subsequent sessions with different topics and recruited colleagues and friends to join them. But these sessions also constituted a great opportunity for the Core team to reflect on its own ability to create impact, and to find support and encouragement in the interpersonal connections that were built during these encounters.

In lieu of a conclusion: training and capacity building for GEP design, implementation and monitoring

Training and capacity building are fundamental for structural change, and efforts devoted to these activities were crucial in all steps of GEP creation and implementation at CES-UC. In GEP design, there was, firstly, a need for relevant stakeholders to embrace the pursuit of gender equality as essential for a fairer, more inclusive and more sustainable institution; secondly, ownership of the GEP would be deeper if said stakeholders were involved in its design. It was to these two dimensions that the team at CES-UC firstly devoted its training efforts, which were continued through the inclusion in the GEP itself of a number of training and capacity building actions encompassing all publics that make up the academic community, devoted to a variety of themes that stood up as particularly relevant during the initial assessment (i.e., inclusive communication, recruitment and promotion, integration of the gender perspective in research and teaching content). What is more, the importance of gender analysis in monitoring and reporting were also part of the general capacity building for gender equality promoted by the Core team at the University of Coimbra.

In addition, the sessions were also an important avenue for members of the Gender Equality Hub and other interested parties to gather – in person or online – in a safe environment, and discuss how they could enhance their own work towards gender equality, often in connection to actions included in the GEP that they could pursue in their faculties or units/divisions. Training, then, was a catalyst for networking, lobbying, finding collective answers to institutional resistances, and support for initiatives taken. Human connections were built and, we like to believe, friendships were created. In that sense, SUPERA training sessions became community-building moments, with a focus on the promotion of Gender Equality.

As we move towards the end of SUPERA, we build on those connections as an essential takeaway from our hard work, and are certain our experience does not differ dramatically from that of other members of the consortium. As our final conference approaches, we look forward for another valuable moment of learning and sharing with the people who accompanied us through this journey, in the certainty that it will not be our last encounter.

Beyond ticking the box: the Final conference recording & presentations are online

The SUPERA project is coming to an end and on Friday, 25th March 2022 (h. 9:30-16:30 CET) our Final conference will take place!

We are proud of our efforts and achievements on gender equality so far and we would like to take the opportunity of the closing event to have an exchange with all the committed colleagues of the gender & science community about lessons learned, promising practices and common challenges for the sustainability of gender equality actions and policies.

Join us on the 25th of March, 2022 at the SUPERA Final Conference Beyond ticking the box: sustainable, innovative and inclusive Gender Equality Plans. The event will be held in a hybrid mode: we look forward to meeting you in Madrid, at the UCM Campus Moncloa (Faculty of Medicine. Room Professor Botella), and online.

Online registration is mandatory: please find the registration form at this link.

You will be invited to choose between the in-presence and the online attendance and you will receive a reminder a few days before the event. Please don´t hesitate to contact the SUPERA Project Team if you have any enquiries: superaprojectoffice@ucm.es

CONFERENCE RECORDING & PRESENTATIONS

The conference recording is accessible via this link on the SUPERA YouTube channel.

The slided used by the speakers are accessible on Slideshare and via the dedicated page of our website.

CONFERENCE AGENDA

9.30 -10.30 Opening

Margarita San Andrés Moya, UCM Vice-Rector for Research and Transfer

Domènec Espriu, Director of the Agencia Estatal de Investigación, MCIN-AEI

Athanasia Moungou Gender Sector Unit D4-Democracy & European Values DG Research & Innovation, European Commission Presentation

10.30 – 11.30 Welcome from the SUPERA Consortium and Keynote speech: “GEPs Eligibility criteria and beyond”

Maria Bustelo, SUPERA Coordinator, Universidad Complutense de Madrid

Marcela Linková, Head of the Centre for Gender and Science. Institute of Sociology of the Czech Academy of Sciences Presentation

11.30-12.00 Coffee Break

12.00-13.30 Round table “Stories of institutionalisation in Universities and Research Centers: inspiring practices”

Moderator: Emanuela Lombardo, UCM

- Mónica Lopes – Centro de Estudos Sociais Universidade da Coimbra: Gender Mainstreaming Monitoring Structure Accountability mechanism of the GEP Presentation

- Ana Belén Amil – Central European University: Increasing the representation of women as Faculty Presentation

- Marta Aparicio – Universidad Complutense de Madrid: Gender Equality Nodes Network Presentation

- Ester Cois – Università degli Studi di Cagliari: Institutionalisation of Gender Equality Delegate position Presentation

- María Pilar Rodríguez and María Jesús Pando – Universidad de Deusto (Project Gearing Roles): Guidelines to mainstream gender in research and teaching Presentation

13.30-14.30 Lunch Break

14.30 -15.45 Round table “Sustainability of GEPs and Networks in Research Funding Organisations”

Moderator: Sophia Ivarsson, VINNOVA

- Massimo Carboni – Regione Autonoma della Sardegna

- Lourdes Armesto – Agencia Estatal de Investigación Presentation

- Carry Hergaarden – Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research Presentation

- Jana Dvorackova – Technology Agency of the Czech Republic Presentation

15.45-16.00 The SUPERA RFOs network: goals and next steps

Lut Mergaert – Yellow Window Presentation

Marcela Linkova – Institute of Sociology of the Czech Academy of Sciences

16.00-16.25 Concluding remarks – SUPERA International Advisory Board

Jörg Müller – Open University of Catalonia, Anne Laure Humbert – Oxford Brookes Business School, Miguel Lorente – University of Granada, Nicole Huyghe – Boobook, Maxime Forest, Sciences Po Paris

16.25-16.30 Closing

Dream it, be it! A joint campaign for 11/02

On the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, 11th February 2022, the EU Sister projects CALIPER, Gender-SMART, SUPERA, LeTSGEPs, RESET, SPEAR, CASPER, ACT, GenPORT, MINDtheGEPs, ATHENA, GRANteD, Gearing-Roles, Gender STI and EQUAL4Europe are joining forces in order to share inspiring stories to encourage other women – and especially young girls – to pursue a career in Research & Innovation (R&I).

On the 11th and 12th of February 2022, we invite you to join our campaign by sharing your stories as women researchers, focusing on what did inspire you them to pursue your career.

The campaign is based on 3 inspiring questions, that are meant to be answered shortly to fit in the poster:

1. What is your professional background?

2. What did inspire you to pursue this career?

3. Who was your role model?

Download the editable Response template [power point format] and share it on social media. You are more than welcome to include photos in your posters. Don’t forget to use our hashtags #DreamItBeIt and #EUSisterProjects and tag us!

On 18/02 an online seminar on Gender Perspective in Teaching at UCM

Recommendations and teaching practices with a gender perspective from the Gender Equality Nodes Network of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid

During this 2021/2022, the Gender Equality Nodes Network of the UCM has worked on the analysis of experiences and practices on how to incorporate the gender approach in teaching. Results of this work will be presented on Friday, February 18, from 10:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m.

The main aim of this event is to provide handy resources and recommendations for the Academic Staff on how to easily incorporate gender equality within classes and teaching tasks and content.

Info and details: https://www.ucm.es/supera/noticias/51479

Registration is required here: https://forms.gle/QHXkSs2tekyin5uJ8

Agenda

10.00 -10.10 Opening

10.10 – 10.45

Introduction to the Incorporation of Gender Equality Perspective in Teaching

General Recommendations in Classroom Management, Methodologies and Evaluation

10.45 – 11.30 Inspiring practices in Arts and Humanities

11.30 -12.15 Inspiring practices in Social Sciences

12.15-12.30 Break

12.30 -13.15 Inspiring Practices in Health Sciences

13.15 – 14.00 Inspiring Practices in STEM

14.00 Closing

Info: SUPERA – Project Office superaprojectoffice@ucm.es

Towards violence-free research organisations: interview with Anne Laure Humbert, UniSAFE project

Anne Laure Humbert, Oxford Brookes Business School, interviewed by Paola Carboni, University of Cagliari

Gender-based violence affects many organisations, with Universities and research organisations making no exception, but despite the scale of the issue, gender-based violence in research organisations is deeply under-reported and under-researched. The UniSAFE H2020 project is conducting the first large-scale study on the topic. Following the joint #SafeResearch4All awareness campaign, we had the pleasure to interview Anne Laure Humbert, a member of SUPERA international advisory board and also a UniSAFE partner.

In which forms can GBV occur in academic and research environments? Who are the victims and the perpetrators? Are the victims of intersectional discriminations more at risk?

The Istanbul Convention highlights four main forms of gender-based violence: physical, sexual, psychological and economic. In the UniSAFE project, we include all four but also consider other forms of violence relevant to the academic and research context such as sexual and gender harassment. We are also interested in emerging forms of violence, such as those linked to the increase in online activities, or the forms of violence not always recognised as violence such as institutional violence.

The issue of gender-based violence is often conflated with that of violence against women. While men represent the majority of perpetrators of all types of violence, and women are the majority of victims of gender-based violence, suffering disproportionate consequences, it is important to stress that both women and men can be perpetrators and victims. Intersectional factors play an important role besides gender alone. Being non-binary, trans, or from a sexual minority for example can increase exposure to gender-based violence, as does working in more precarious positions or not studying in one’s country of origin.

Is data available on how many people experience harassment and GBV in academia in Europe?

Few data are available on gender-based violence generally across Europe, with even fewer information available in the context of academic and research institutions. The UniSAFE project will provide the first large-scale study on this topic, providing both quantitative data through a survey carried out in 45 institutions across 15 countries and in-depth qualitative data through case studies of institutional responses in 15 countries and interviews with researchers more at risk of gender-based violence. The project is currently launching a call for researchers having experienced or witnessed gender-based violence at an early-career stage, on a non-permanent contract, or as an internationally-mobile student or staff, to share their experience in an individual interview. Find out more about the interviews.

These results will be contextualised through an extensive mapping of legal frameworks and policies at the national level and within the institutions taking part in the research.

The project has already delivered 33 country reports on national and regional policies on gender-based violence in universities, research institutes and research funding organisations, that are publicly available at this link.

What does it mean to switch from an individualist perspective to an organisational violence perspective?

Gender-based violence should not be understood solely from an individual perspective, where the traits or behaviours of either victims or perpetrators are the focus of attention. Instead, it is important to understand violence as a structural issue, and part of a system that produces and reproduces inequalities between groups, including on the basis of gender. Organisations, such as for example universities, create and uphold the norms that shape this system of inequalities. Studying organisational violence therefore means also putting the focus on the environment, and what it does to enable or challenge gender-based violence at the individual level, but also how it can be violent towards individuals in its own right. This is visible when institutions not only fail victims, but in fact revictimise and blame them in turn rather than address the problem of violence itself.

What are “violence-free” organisations and workplaces?

International standards such as the ILO Convention n.190 recognise the right for individuals to a world of work free from violence and harassment. The UniSAFE project aspires to contribute to the creation of violence-free universities and other research organisations. This can be achieved by developing policies and practices to counter violence, promoting violence-free cultures and enable leaders to support this. It is not only about eradicating different forms of violence, but also about creating and sustaining structural change of an environment where individuals feel – and are – included and safe.

How can a research institution address the issue of GBV, for instance including specific actions in their GEPs? How should institutions challenge the power structures behind GBV?

The Horizon Europe Guidance on Gender Equality Plans – aimed at supporting institutions to meet the Gender Equality Plan (GEP) eligibility criterion of Horizon Europe – recommends five content-related (thematic) areas, including measures against gender-based violence, including sexual harassment. It is likely that this will lead to an increase in the number of institutions in Europe that develop and implement actions to tackle the issue of gender-based violence. A danger, however, is that if this is only done as response to a financial incentive such as access to funding, then it will fail to properly address the power and inequality structures that are at the root of gender-based violence in the first place. It seems that many institutions are realising the extent and importance of the problem as a result of societal campaigns such as #MeToo, but all too often only putting meaningful processes and structures in place in reaction to critical incidents and/or media exposure. On an optimistic note, the UniSAFE will provide many evidence-based tools by the end of 2023 for institutions that seek to eradicate the problem and change their culture, and thus create the shift in power relations that is needed to create inclusive and safe universities and research organisations.

The project’s latest developments are regularly shared on Twitter (@UniSAFE_GBV), LinkedIn, and through a quarterly newsletter to which you can subscribe here.

Unconscious bias in research funding: a new webinar for RFOs on December 16th. Register now!

How research funding organisations can intervene to avoid unconscious biases in their work? A new webinar designed for RFOs will take place on Dec, 16th h. 11-12:30 CET.

The first speaker, Maxime Forest (Science Po, SUPERA Monitoring and Evaluation partner), will explain the different aspects of RFOs’ work where unconscious bias may slip in and influence ultimate effects.

The intervention of the second speaker will be of a more practical nature: Carry Hergaarden, from the Dutch Research Council (NWO), will share NWO’s experiences with the ‘inclusive assessment’ initiative. This practice is being promoted by the European Commission in its recently published “Horizon Europe Guidance on Gender Equality Plans”.

After the two presentations, there will be time for questions and answers.

Click here for the registration form

This is the 4th webinar organised by SUPERA and specifically dedicated to gender equality in research funding organisations.

SAVE THE DATE! On March 25th 2022 the SUPERA Final Conference: see you in Madrid & online

Time to save an important date on your calendars!

On Friday, 25th March 2022 (h. 9:30-16:30 CET) the SUPERA final conference will take place. The sustainability of institutional change for gender equality will be the core topic of the day.

We are glad to announce that Marcela Linkova is confirmed as keynote presenter. Stay tuned to know all the speakers!

The event will be held in a hybrid mode: we look forward to meeting you in Madrid, at the UCM Campus Moncloa, and online. A registration form will be available in the next weeks.

You are more than welcome to share the news with your colleagues!

Gender equality in R&I ecosystems: engaging external actors in institutional change processes

By Maria Sangiuliano (Research Director and CEO at Smart Venice, CALIPER scientific coordinator)

In recent years ERA policies on gender equality in research have expanded their scope to cover innovation at large. This is reflected in several policy documents, and responds to an overarching emphasis on bridging academic research with society and the economy, an orientation that is visible in the Horizon Europe Work Programme and the value attributed to research impact thereof.

More specifically, the European Commission most recent policy directions on Gender Equality in R&I and institutional change that seek for ‘inclusive’ Gender Equality Plans, refer to “multi-sectoriality” as one of the dimensions (along with intersectionality and geographic inclusiveness) on which a forthcoming Horizon Europe funded Centre of Excellence on gender in R&I and the next generation of sister projects on institutional change will be called to investigate, generate knowledge, and experiment about.

The H2020 CALIPER project was designed and is now implemented, since 2020, having multisectoriality as its key specific feature to be embedded in all steps of the institutional change process, from the internal assessment to the GEPs design and implementation phases, as well as in monitoring and evaluation. In concrete, this has implied for example an expanded scope for the internal initial assessment studies: Third Mission, Technology Transfer, Science Communication have been included to the usual recommended areas that are also part of the Horizon Europe requirement on GEPs. Also, the internal assessment/audits have been complemented by ‘external assessments’ and a gender sensitive mapping of innovation ecosystems using different methods including Social Network analysis, by each one of the 9 partner RPOs and RFOs, according to a specific set of indicators and to map.

Adopting a quadruple/multiple helix and gender sensitive approach to innovation ecosystems, all the 9 RPOs and RFOs have then formed their own “CALIPER R&I Hubs” engaging with national, regional and local authorities, private companies, social innovation actors and civil society (including feminist) organizations, as well as high schools and media. A co-creation process running in parallel with both internal and selected and motivated external actors has led to the design of GEPs. While the plans clearly keep their main focus on generating internal sustainable change, they include collaborative initiatives to be implemented in synergy with external actors: the purpose is thus to promote and support gender equality inward at the CALIPER partner organizations, while having an outward and multiplying effect at the territorial level.

At the consortium level, continuous efforts have been devoted since the very first phases on studying and sharing good and promising practices and criticalities potentially emerging from this approach, enquiring gender expert organizations, communities of practices, sister projects (SUPERA included), and the Advisory Board members. Specific, hands-on and interactive training sessions and modules have been delivered to partners including simulations on the engagement strategies to be devised.

All in all, we believe in the transformational potential of a multi-sectorial approach to gender equality in R&I, and at the same time we are aware of potential risks and tensions that might arise.

Even if the experience from the project is still ongoing as most of the partners have recently started the first GEPs’ iteration with some delay mostly due to the covid19 pandemic, our learning path on these matters can be summarized as follows:

- It is important to re-interpret and re-define the multisectorialy/intersectorial dimension of inclusive GEPs going beyond the mere interaction with the private sector, relying on gender and feminist interpretations of innovation ecosystems and, including those ‘marginal’ actors whose voices and positions are often more critical of mainstream (often gender blind or neutral) innovation policies and discourses.

- Synergy processes, alliances and exogenous change factors can be featured as potential levers, generating exchanges of gender expertise, facilitating internal consensus building particularly from high management positions, and their buy-in towards gender equality.

- At the same time, risks are to be taken into account, and efforts well balanced as external factors can become scapegoats to avoid taking full responsibility towards internal change, or lead to losing focus from the internal change dynamics that have an already high level of complexity to handle.

If you have experience and methods to share, we are more than interest to learn and interact on multi- inter-sectorial approaches to institutional change for gender equality, so do not hesitate to contact us!

Gender-based violence in research and academia: a joint awareness campaign with the sister projects

Leveraging on the International day for the Elimination of violence against women (25 November), the H2020 UniSAFE project on gender-based violence in university and research organisations has joined forces with sister projects involved in structural change for gender equality in research and academia (SUPERA, SPEAR, TARGET, TARGETED-MPI, GEARING ROLES, RESET) as well as with other projects, organisations, and individuals, to raise awareness on gender-based violence in research and academia through a campaign running between 22 and 29 November 2021.

Gender-based violence is a complex, prevalent, persistent feature and force in many organisations, with pandemic proportions. Violence, violations, and abuse may be physical, sexual, economic/financial, psychological – online or offline – and can include gender or sexual harassment.

Universities and research organisations are not exempt from this pandemic. Specific organisational structures can even create conditions for hierarchies of power that are structured by gender and age and regularly underpin violence. While gender-based violence deeply impacts individual lives, it also has serious social, economic, and health repercussions on organisational and social levels.

Despite the scale, the political significance and the growing interest in academia, gender-based violence in research organisations remains largely under-reported and under-researched. It also often remains unspoken.

A selection of the contents shared during the #Saferesearch4All awareness-raising campagin can be found at this link.

From 22 to 29 November, all projects, organisations, and individuals intent on eradicating gender-based violence in academia and research organisations are invited to actively post on social media using the hashtag #SafeResearch4All.

Media, articles, reports designed or collected by UniSAFE and sister projects have been made freely available in an Awareness-raising Toolkit. When sharing UniSAFE results, full acknowledgement of the project and authors must be mentioned, as stated in the introduction.

Fighting gender-based violence in academia and research starts with bringing the issue to the surface, paving the way for victims to speak out, and for all students and research staff to be proactive role models in this respect.

Contact: Colette Schrodi, European Science Foundation, UniSAFE communication officer: cschrodi@esf.org

Gender@UC & SUPERA: the University of Coimbra at the European Researchers Night

By Claudia Araùjo, Universidade de Coimbra

On September 24th, the SUPERA team at the University of Coimbra participated in the European Researchers Night.

In Coimbra, we organised a spot in one of the busiest streets downtown with another project at the University, GendER@UC EEA Grants, which focus on promoting the integration of the gender perspective in research. We opted for a participatory approach aimed to highlight the importance of gender mainstreaming in higher education, and invited a number of other inspiring gender-sensitive (action)research projects and initiatives rooted or ongoing at the UC to collaborate with us.

We present below the activities developed by each of our partners:

SUPERA – CES/UC

We decided to focus on the importance of the Equality, Equity and Diversity Plan of the University of Coimbra and created both a presentation and an interactive kahoot quiz that we used to engage with our audience. In the quiz, we were able to communicate both the need for Gender Equality Plans in higher education institutions (through questions about horizontal segregation, work-life balance, etc.) and the impact the plan has already had in the leadership structure of the university itself (through questions about the percentage of women in leadership at the UC both before and after the approval of the GEP). We also highlighted, through practical examples, the overarching influence of the GEP, demonstrating as it affects the whole academic community – and also the society as a whole. Another aspect whose importance we reinforced was the importance of using inclusive communication.

Figure 1. The flyer for the Supera & GendER@UC spot at the European Researchers Night

GendER@UC EEA Grants – Institute for Interdisciplinary Research at the University of Coimbra

The project GendEr@UC spoke about the importance of integrating the gender perspective in research content, through a role of examples of projects whose results were skewed due to its absence, as well as those which have successfully integrate gender into the design, analysis and presentation of results, thereby producing more inclusive, realistic, and useful research overall.

Pandemic and Academy at Home – CES/UC

The Pandemic and Academy at Home project proposed an interactive game of questions and answers about the differentiated impacts of the pandemic on the research and teaching activities of women and men in Portugal, as well as questions about the integration of the gender dimension in scientific research and the University of Coimbra.

Glass Frontiers

The Glass Frontiers project proposed an interactive presentation on how gender stereotypes affect educational and professional trajectories of men and women.

Phoenix – Citizens Voices for a Greener Europe

This project, which has recently received a grant from the European Commission, discussed the importance of integrating women in the public discussions on the Green European Deal, in particularly in citizen assemblies, by highlighting the importance of the gender perspective in addressing the climate emergency.

Figure 2. SUPERA in action at the European Researchers Night

It was also important for us to present the work of initiatives currently rooted at the University of Coimbra that are working to break stereotypes and increase the presence of women in scientific areas where they remain underrepresented, so we invited the Coimbra delegations of Women in Engineering and Girls Who Code to collaborate with us. Both were represented by both female and male students, thereby demonstrating that gender equality in higher education concerns both women and men.

Women in Engineering

Women in Engineering discussed the importance of including women in engineering and the gender perspective in the work of engineers through interactive quizzes, deconstructing gendered stereotypes that prevail in women’s access to STEM areas.

Girls who Code (As Raparigas do Código)

Girls who Code presented two separate activities – they had an interactive game about Gender in IT professions and brought the theme of stereotypes in artificial intelligence to discussion, an increasingly important issue in the network society, through a practical demonstration on facial recognition.

We were also lucky to count with the collaboration of the State Secretary for Equality, Rosa Monteiro, and the President of the Commission for Citizenship and Gender Equality, Sandra Ribeiro, who both sent videos in support of our event, and also featured some presentations produced by Journalism and Design students about gender equality at the University of Coimbra and in IT start-ups/companies.

Overall, this was a fantastic opportunity for us to present a collective narrative on why gender needs to be a factor in university governance overall, and we were lucky to spread the message to both the academic community and the general population in the city, including younger people. This was a successful occasion to disseminate our project to an audience that is normally removed from it, and our presentations and practical exercises certainly gave the public some food for thought on Gender Equality.

Gender-sensitive data collection and monitoring: the experience of CEU

Ana Belen Amil, Central European University, interviewed by Paola Carboni, University of Cagliari

Implementing gender equality policies in academic environments requires the availability of gender-sensitive data to support evidence-based decisions. The challenge to properly analyse such data is huge, if we consider that not only it should be systematically collected and stored, but also monitored and updated over time.

With this in mind, following the experience developed during the gender equality baseline assessment performed within SUPERA, CEU’s Gender Equality Officer Ana Belén Amil and CEU’s Institutional Research Officer Anna Galacz developed a “Handbook of gender-sensitive data collection and monitoring”.

The drafting process required the involvement of several university units, responsible for the collection and storage of different data sets, and the result is a tailor-made, step-by-step guide to data collection and management, with a solid gender equality background. The Handbook is currently under revision, in collaboration with prof. Anne Laure Humbert, researcher at the Centre for Diversity Policy Research and Practice at Oxford Brookes University and member of SUPERA’s international advisory board, and will be publicly released in the next months.

In the following paragraphs, Ana Belén Amil provides us with several highlights about the process that led to the development of the Handbook and some practical examples and advice.

What does “gender-sensitive data collection and monitoring” mean?

In short, gender-sensitive data collection means that gender is systematically included as a variable at the moment of collecting data on individuals. It is also know as “gender-disaggregated” data. Without it, it is impossible to assess the status of gender equality in a given context (in an institution, in a country, in a continent, for example) for a particular indicator. Once the assessment on that indicator is done, and an gender inequality is found, different types of measures shall be applied to improve such inequality. During the monitoring phase, data is collected and analysed once again on that particular indicator to assess if the measures taken had led to progress in gender-related terms (and if so, to which extent). Monitoring can also occur for indicators in which no inequality was found but that, according to research, tend to show gender inequalities. This way we can closely follow an indicator and be aware of any deterioration that might occur.

Can you give us some practical examples of why is it important for a research institution to collect data in a gender-sensitive way?

Collecting data in a gender-sensitive way only makes sense if a research institution is interested in promoting gender equality among its staff, students (if we talk about a university), research content and knowledge transfer. This might sound as an obvious interest on the side of HE&R institutions but, depending on the particular (political) context in which the institution is embedded (at a national or regional level), improving gender equality might not be a goal for the institution or might not be easy to pursue.

Assuming that the interest (and feasibility) are there, then there is no way to take evidence-based measures for the promotion of gender equality without a proper assessment to know where we are standing vis-à-vis a variety of indicators. To give an example: gender-disaggregated data on salaries is paramount to diagnose gender pay gap in an institution and act upon any disparities that such indicator might show. Collecting the gender of principal investigators across research teams will enable us to analyse gender disparities in leadership positions and design measures to correct them if needed.

How did you became aware that managing data with a gender-sensitive approach is a key asset for a university?

This became evident to me during the assessment phase of the SUPERA project. We had developed many indicators, and when we started approaching different Units in the University to provide us with data to run the calculations, we found that many of this data was not collected at all, was collected in a way that did not allow for statistical analysis (i.e., on paper, no digitalization), it was inaccurate, or dispersed across different units without a central database. This made it impossible (or too time-consuming) to analyse data and see how badly (or well) we were doing in certain gender equality indicators. That is when the idea of the Handbook came up: as a response to all data gaps that were found during the diagnostic phase.

Which university offices are involved in such an in depth-analysis?

It very much depends on the University and its structure. In the particular case of CEU, lots of offices are involved since the scope of the data needed is very wide. Human Resources Office and Student Records Office – Admissions Office collect data on employees and students respectively. Academic Cooperation and Research Support Office collects data on research projects (externally funded). Institutional Research Office is key for performing calculations. This list is not comprehensive but covers the offices with the highest involvement in data collection.

Which are the key action areas in which the monitoring indicators are organised? Can you describe them with some examples?

The data collection and monitoring are organised in key action areas that follow the European Commission’s suggestions with some adaptations that were more suitable for our University. Some examples of areas and their indicators are:

- Gender Equality in leadership and decision making: gender distribution in leadership positions (Rector, Provost); gender distribution in the Senate – both of them from a historical perspective.

- GE in recruitment, retention and career progression: gender distribution of the average time it takes for staff to be promoted, gender distribution of academic staff turnover, gender distribution of Faculty recruitments.

- Work-Life Balance: gender distribution of average time taken for parental leave.

- Gender in research and knowledge transfer: gender distribution of researchers in research teams, number of courses that incorporate a gender dimension in their syllabi.

- Sexual harassment: number of cases registered, severity of the cases.

How can you adopt a non-binary and intersectional approach in data management?

For a non-binary approach, we made sure to adapt our IT systems to allow students to freely describe the gender they identify with. For employees this is more difficult since the software that processes employee data does not give that option; this is still a matter to be solved. Regarding intersectionality, this is much more complicated. In theory, data collection should include other variables besides gender, such as race/ethnicity, disability, age, nationality, etc. This is a very difficult task in practice; it is already extremely challenging to collect gender data systematically, even more so to collect data for variables that were never considered for analysis. Data on race/ethnicity is particularly challenging due to the sensitivity of the topic, so for the moment we are using some (imperfect) proxies for it, such as nationality and country of birth.

Which are the most challenging aspects of introducing this approach in an institution? Do you have any practical advice to give?

I found two main challenges: collecting data under GDPR, and the lack of centralized database. Collecting and analysing data in a way that is GDPR compliant should not be, at least in theory, a complicated task. But practice showed me that due to a (sometimes) too restrictive reading of general data protection regulations, the task becomes highly bureaucratic and therefore very time-consuming. I do not think there is a way around this other than getting familiar with the content of these regulations to be clear about what can and cannot be done in terms of data collection/processing.

Regarding the lack of a centralized database (in our case this only applies to the employee body; student data is much better organized), my suggestion is to work intensively with the IT Department and Human Resources Office to come up with strategic solutions to put the data “in order”. This will not only benefit gender equality related assessment but also the strategic planning of the University as a whole. It is important to raise awareness on how important (gender-sensitive) systematic data collection is for the running of the institution.

Another challenge, but this is not specific to gender-sensitive data collection, is the low level of prioritisation it tends to receive. Unless there is an urgent need derived from other aspects of the functioning of the university, this task is so time consuming and sometimes overwhelming that it gets dropped to the bottom of the list.

Is it possible to introduce gender-sensitive data management on a low-budget basis?

If by budget we only refer to financial resources, I would say yes. If we include internal human resources as part of the budget, my answer would be: it depends on the mess that the university has in terms of data management. The more chaotic and unsystematic, the more work in terms of human involvement will be required to bring order to the chaos. And this is of course specific to each institution.

What sources provided you inspiration for this work? Can you recommend some reading in particular?

The main source of inspiration was the work done by several sister projects of SUPERA, who had already developed a compilation of indicators and shared them in public deliverables. Since one of the core principles of SUPERA is cumulativeness, we built up from what other projects have done before and adapted it to our own institutional context. Of course we let go of some indicators that were not relevant for CEU, while we also added others that were not present in previous compilations, but we don’t have to reinvent the wheel each and every time.

Our main resources were the deliverables of Gender Diversity impact (GEDII), Plotina, Baltic Gender, Target, GARCIA, EFFORTI, Gender Net, and of course She Figures.

The XI European Conference on Gender Equality in Higher Education is approaching

By the Local Committee of the 11th GEHE Conference

The Spanish institutions organizing the 2021 online edition of the GEHE Conference (15th – 17th September) are proud to present an inspiring and diverse program with high-level contributions received from the gender & science community and practitioners. Our goal is to provide the space for them to share their knowledge and expertise so that the public authorities can design better and more effective policies.

When the organizers of the XI GEHE Conference had to take the difficult decision to postpone the 11th GEHE Conference to September 2021, the situation was uncertain both due to the global health emergency and in relation to the organization of the Conference. Today, after considerable efforts to launch a new call for abstracts in 2021 and to adapt the whole program to an online event, the organizers are glad to communicate that the agenda for the upcoming 11th edition of the GEHE Conference has been published in our website and the registration has been closed.

Since the beginning of 2021, the Women and Science Unit of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, the Ministry of Universities, the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology and the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, with the financial support of the Spanish Institute for Women, resumed work on the organization of the Conference. First, the organizers decided to open a new call for abstracts in order to give the opportunity to present new works. Indeed, given the importance acquired by the impact on the confinement in women’s research careers and the sex/gender analysis of research on covid-19, the organizers added a new topic. Then, our international scientific committee once again proceeded to evaluate the new proposals submitted following the same evaluation criteria. Taking into account both 2020 and 2021 call for abstracts, this 11th edition received more than 200 proposals, what can be considered as a success of the Conference given the difficult conditions. The organizers are grateful to the scientific community and practitioners for their committed work revealing persistent inequalities and producing valuable knowledge to build better science and innovation systems.